Part 3: Supporting Students in Making Inferences

So much of what students must do to understand, and then be able to critically analyze the written word and world around them relies upon their ability to infer. We make inferences all the time, and, still, making our first inference was never as simple as defining an inference and then just doing it.

In her book, Beers gives the following example:

| Read the following paragraph and then, on a scrap piece of paper, write what you think is happening in the text:

He put down $10.00 at the window. The woman behind the window gave $4.00. The person next to him gave him $3.00, but he gave it back to her. So, when they went inside, she bought him a large bag of popcorn. When I read this paragraph I see a man and a woman who are on a date at the movies; I can figure out from the money he gave the lady behind the window and the amount that he got back that the tickets are $3.00 per person, so they must be going to a matinee. Furthermore, the woman with the man doesn’t want the man to buy her ticket. He won’t accept her money because he’s being either nice or proud. But I think nice because when they get inside she buys the popcorn because she doesn’t want him to pay for everything. |

How did your interpretation compare to Beers’s? Even if it differs, you both did one thing to make sense of this text; you both made a lot of inferences.

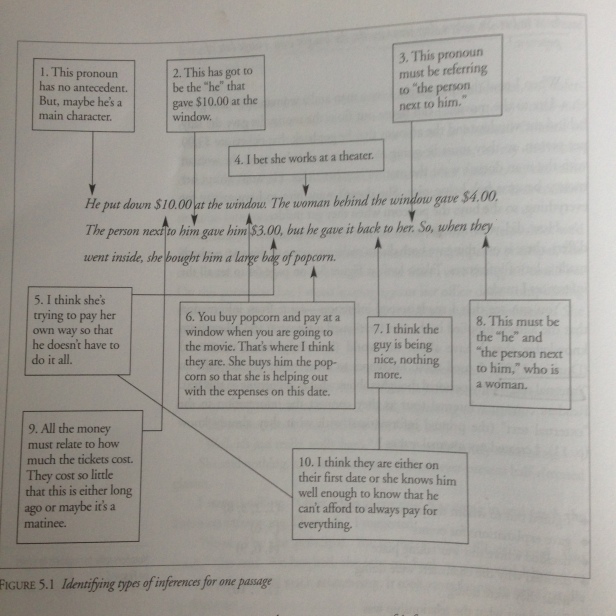

Let’s look at a breakdown of the inferences you made (the numbers refer to the image below):

- Figured out to whom the pronouns referred to (1, 2, 3, 8)

- Gave explanations for events (5, 6)

- Decided where this was taking place (4, 6, 9)

- Decided why the characters were doing what they were doing (5, 7, 10)

- Figured out what the relationship was between the characters (10)

- Used your own knowledge about the world to provide details (6)

Check out this visual:

When we analyze our own inferences, then we can begin to show students all the steps involved in making an inference! Here’s a list of some of the most common inferences that skilled readers make AND comments or questions you can pose to help students make certain types of inferences:

| Skilled readers… | Skilled teachers ask…

(these do not necessarily directly correspond) |

| 1. Recognize the antecedents for pronouns

2. Figure out the meaning of unknown words from context clues 3. Figure out the grammatical function of an unknown word 4. Understand intonation of characters’ words 5. Identify characters’ beliefs, personalities, and motivations 6. Understand characters’ relationships to one another 7. Provide details about the setting 8. Provide explanations for events or ideas that are presented in the text 9. Offer details for events or their own explanations of events presented in the text 10. Understand the author’s view of the world 11. Recognize the author’s biases 12. Relate what is happening in the text to their own knowledge of the world 13. Offer conclusions from facts presented in the text |

“Look for pronouns and figure out what to connect them to.”

“Figure out explanations for these events.” “Think about the setting and see what details you can add.” “Think about something that you know about this [insert topic] and see how that fits with what’s in the text.” “After you read this section, see if you can explain what the character acted this way.” “Look at how the character said [insert a specific quote]. How would you have interpreted what the character said if he had said [change how it was said or stress different words]?” “Look for words you don’t know and see if any of the other words in the sentence or surrounding sentences can give you an idea of what those unknown words mean.” “As you read this section, look for clues that would tell you how the author might feel about [insert a topic or character’s name].” |

Putting this into ACTION!

In an upcoming post about “during-reading” activities that support student understanding, I’ll share more about a strategy called “It Says, I Say”. This structure in general helps students pause and think about what they’ve just read. Some students, however, need additional help in making inferences. For those students you might try the following activities:

- Put the list above of different types of inferences that independent readers make on a large chart up in your classroom. Refer to that list often. The idea is to turn the word infer or inference into something more concrete, something that students can point to.

- At least once a day, read aloud a short passage and think aloud your inferences. Have students decide what times of inferences that you are making. Passages can be the first couple of paragraphs from a selection in your literature book, something from a magazine, a paragraph from a novel you are reading. Two-Minute Mysteries by Donald Sobol is a great choice!

- Remind students that authors don’t expect readers to create inferences out of nothing. Author’s provide information that they want the reader to use to make meaning. Give students sample sentences and have them differentiate between the literal information and what the author is implying through the use of context clues.

- Read ahead in the text that students will be reading (do this always) and make notes of all the types of inferences you made to help the text make sense. Pull some passages from your text and put them on an overhead transparency, then perform “Syntax Surgery” on them.

- Syntax Surgery: As you think aloud the inferences you make, mark up the passage so students can see how pronouns relate to nouns or how you use the context to define unknown words or how you add details to events described in the passage.

- Cut out some cartoons from the newspaper and put them onto a transparency or under a document camera. Read them aloud and then think aloud the inferences you make that allow you to perceive the cartoon as funny. Then let kids cut out their favorites and bring them in and do the same thing! You can move all the way up to political cartoons, which often allow for discussions about how making inferences is next to impossible if you don’t have the right background information.

- Show students signs (or bumper stickers) and have them write the internal text that comes from the external text. Have students refer directly to the list of inferences to share what inferences they are making in order to write the internal text.

Share in the comments below how these strategies work in your classroom!