Modified and adjusted from this guide.

There is no denying that we are moving towards the classroom that ever-values differentiation and personalized learning. We know that when students are met in their ZPD with skill-building and pedagogical practices that support them as learners, they grow further faster. This is why models such as Teacher’s College Readers and Writers Workshop has TAKEN OFF, moving from primary grades to secondary grade classrooms. This is why models like Summits Personalized Learning Tool and leveraging of pre-existing online content that can be accessed through the 21st Century methods (that we, as teachers know well…hello, Professor Google!) are spreading across charter networks across our country. However, even as our classrooms move from a 50:50 to a 20:80 model of full group to independent choice reading and writing, we cannot and should not lose sight of this 20%. This 20% is where we, as teachers, make deliberate and informed choices about the central content of our classrooms, the texts that students should all read, and read together, because of the richness of content, complexity, and conversation.

Planning a novel can also be daunting, especially as a new teacher. I will not expound here upon my first novel planning/instruction here, but ask me sometime. It was, and remains, a humbling experience. Below I’ll share a 9-step process that can help you prepare and plan a novel unit for your classroom that will ensure that your lessons are focused and aligned to the big questions and ideas that you want students to be asking and engaging in.

Step 1: Read the Novel

I cannot emphasize this enough. It might seem difficult to find the time to fully read the novel(s) that you plan to teach, but it is a must. Reading ahead of time allows you to find the best novel for your students at that point in time. Given that you and your students may only read 4 novels together over the course of the year, you should know each of these novels in and out, front to back and front again. Just as you wouldn’t paint your entire house a color that you’ve never seen before or you’re uncovering as you go…you don’t want the three to eight weeks to similarly be filled with surprises and missed opportunities (and regret).

When reading the book(s) that you’re choosing from (I often would read 3-4 on the same themes or topic), ask yourself the following questions:

- Why this book?

- Why for my students? At this point intime?

- What are the messages that my students will take away? What are the questions with which they will grapple?

Some helpful metrics for choosing a book include, but are certainly not limited to:

- The text is a classic that continues to be read by students today and is relevant in its topics and themes.

- The text is well written and contains strong examples of literary devices, perhaps modeling particular strength in characterization, point of view, dialogue, plot, development and conflict.

- The text contains at least one universal theme that can be integrated into a larger conversation or unit of study.

- The text speaks to student experiences, interests, concerns, or social issues.

- The text is grade-level appropriate—in both content and complexity. While students’ independent books should (generally) be in their ZPD, class texts are meant to be more challenging, which is why you are reading them together.

- The text aligns or supports Common Core State Standards

In all honesty, you’ll need to read the book more than once. But reading the first time through, just to (re)build comprehension and plot awareness is not a step to skip. More on the re-reading below!

Step 2: Determining 2-3 Universal Themes

A novel that is compelling and worthy of full-class study must be memorable at the thematic level. It must contain a message to which humans across cultures and communities can connect. It is the level of learning that sits above the plot points. It’s what makes a story about a dog pulling a sled a story about determination, struggle, and identity; a story about a Latina girl in Chicago riding bikes and kissing boys about growing up, finding yourself, losing innocence.

Whatever the book, connecting it to 2-3 universal themes will support you in drafting lessons that engage students in bigger conversations about the world and society regardless of the main character. It will also give you a focus and a lens to read through, providing direction for your novel study.

There is also some debate about which comes first—book or theme. There is no “right” way. In many instances, which comes first is dependent on the supports you have in place at your school and in your districts.

Depending upon your autonomy in planning your units of study, this step can look very different. Here are some scenarios:

- I have no guidance, just standardsà I determine themes for focus

- I have a unit assessment from my school/district that focuses on a particular themeàI determine how my chosen text fits into this theme

- I have been given a book to teach but no assessmentàI determine themes for focus

- I am given a book and the themes through my school/district pacing guideà I determine how I will connect these themes to the experiences and interests of my students and the world.

For this purpose, I will follow a medium-support model—you are given an end assessment task. This question is not contingent upon reading a specific book, but does require citing specific texts to support your answer (think AP Lit Exam).

| Culminating Assessment Task: Citing and explaining at least three separate examples from the texts you’ve read during this unit, answer the following question in an argumentative essay: In many works of fiction and non-fiction, we consider the benefits and injuries of knowledge over ignorance. Consider the texts that you’ve read in this unit. Do you believe that knowledge is truly power worth having despite its pains? Or is ignorance truly bliss? Make sure that you cite and explain at least three specific examples from two different texts that support your answer. |

To dive deeper into the advantages of using themes, check out this resource here.

Step 3: Develop Guiding Questions

With your novel and themes in tow, your next step down the yellow brick road of novel planning is to develop guiding questions. Guiding questions, also called essential questions, capture the concepts, issues, and understandings that are most significant to your selected themes. With younger grades, you can develop these questions ahead of time; with older grades, you might have your students develop these questions as you read. Questions can then be used later for assessment!

Strong guiding questions tend to have similar criteria. Here are some thoughts on what makes a strong guiding question:

- Open-ended without a clear right answer.

- Thought provoking, controversial. These should be questions that spark debate and encourage students to read and re-read closely to develop a strong argument.

- Require students to draw on knowledge from multiple sources, including their lived experience.

- Can be revisited and engaged in throughout the unit to engage students in ongoing dialogue and discussion

- Lead students to pose additional questions

| Topic: Knowledge—knowledge is facts, information, skills acquired by a person over the course of their lifetime. This can be a collection of lived experiences or more abstract information and understanding. It can be practical and/or theoretical. It leads to an individual’s understanding of the world in which he or she lives. |

| Novel: The Giver by Lois Lowry |

| Theme: True choice is impossible without knowledge. While knowledge can bring enlightenment and joy through choice, it can also bring pain. |

| Essential Questions:

· How is knowledge a force for good and evil? · Are the risks and challenges associated with more knowledge worth it? · How does acquiring knowledge impact an individual’s quality of life? · When, if ever, is it better to remain ignorant? |

Click here for some topics, themes, and aligned essential questions!

Step 4: Deconstruct the Novel

In addition to reading the novel for understanding, once you determine your theme and essential questions, you’ll want to return to the novel and consider how to break it down for your reading and engagement with students.

Here are a few strong strategies you can use to set yourself and your students up for success:

- Chunk the book into 3-5 sections. By determining large buckets that different parts of the text breakdown roughly into will help you think about where to place formative and interim assessments, as well as supplementary readings throughout your unit.

- Create anticipation questions for each chapter. What are questions that will help refresh your students’ minds from the last chapter and cue them for the new chapter?

- Label each page with a “page title”. This strategy helps you, as the teacher, flip through to find key events; it also is a great summarizing task for students.

- Jot down questions throughout the chapter. While you’re re-reading, jot down questions that you think will be key for students to engage in and answer in order to build knowledge and information towards answering the essential questions and formulating an opinion about the theme. This will also help you form your response to literature questions that students will engage in throughout the unit to help them build in their analysis and critical thinking in preparation for the culminating assessment task.

- Mark any literary devices. This will be key for your ability to piece together the author’s craft and structure moves throughout the novel and support your students in noticing them—both for their own ability to analyze the impact on the text and emulate them in their own writing.

- Don’t be afraid to use supports. I love the website com. In fact, I use it for theme creation and pressure testing as well. Shmoop is home to literary analysis of many novels, and this can help you build theme awareness and develop strong questions. Proteacher.net and Betterlesson.com are also great resources to provide ideas! Protect yourself against the desire just to pull and put these lessons into place. Make them your own! Make sure you align the ideas of others to what you’re really working towards with your students.

Step 5: What Else Are We Going To Read? Finding and Aligning Supplementary Resources

We continue to read these novels in a full-class setting because we believe that they are worth the time and the engagement of all students. In order for these novels to be as sticky and impactful in the lives of our readers, it is also important to couch them in supplementary materials that help contextualize and amplify the messages and conversations. I find additional articles, short stories, videos clips, interviews, and photos to add breath and depth to each novel we study. I find it helpful to use a matrix with the novel at the center to plan out the selections for each unit.

| Harrison Bergeron by Kurt Vonnegut (short story) | Antibodies Part 1: CRISPR, Radiolab (podcast) | The ABCs of the German School System, Expatica (article) |

| Utopia by Wislawa Szymborska (poem) | The Giver by Lois Lowry (central text) | Book Burning/Banning (article) |

| Excerpts from Minority Report (movie and short story) | How Can You Control Your Dreams, Scientific American (article) | Censorship: China/North Korea, pros and cons (article) |

Depending on how much long the central text is, how many weeks you’ll be spending on the unit, and the space you have for additional texts, this matrix could be larger. I prefer to assign an article of the week—something non-fiction from a reputable news source—that students get on Monday and read that evening for homework; we discuss Tuesday and imbed into our discussions of the central text throughout the rest of the unit. To see more on this article of the week structure, check out this page from Kelly Gallagher’s website.

You can also use articles and supplementary materials to start a discussion. I oftentimes modify and add to this matrix depending upon current events and new writings. Maybe I find my class tending towards one opinion. Finding an article that plays devil’s advocate can add some complexity to our discussions and our reading of the text.

Step 6: Identify Literacy Targets

Now that you’ve got the energy and spirit of your novel unit mostly determined, it’s time to zoom up and out and figure out where your literacy targets and standards fit. Some prefer to do this in a different order, and that is absolutely a-okay! I prefer to think big ideas and then align to standards, but I know that this isn’t for everyone—especially if you have key standards you MUST hit in the unit. One thing to remember about ELA standards is that they spiral across genres and units in many cases. You will not teach “theme and central idea” one time. You will teach it over, and over, and over throughout the year. See each unit as a chance to focus on identifying HOW this particular author builds this particular theme.

When it comes to this HOW, this is where literacy targets come into play. Here is a short, and certainly not exhaustive list of possible reading targets. For a longer list, click here.

Reading skills and strategies to target:

- Previewing

- Summarizing

- Predicting

- Organizing thinking using a graphic organizer

- Recognizing parts of speech

- Determining vocabulary using context clues

- Comparing and contrasting

- Making inferences

- Determining cause and effect

The list goes on. And there is an equally long list for writing!

Step 7: Collect and Develop Instructional Resources

When you’ve chosen you literacy targets and strategies, you can now align your chapters and chunks of the text to those targets and strategies. You can make key choices about the parts of the book that are BEST for certain targets.

| In The Giver, for example, a key strategy for understanding the theme is to compare and contrast Jonas from the beginning of the book to the middle of the book to the end of the book. In order to do this, I know that my students need to be able to make inferences, in particular inferences in order to characterize Jonas at multiple points in the reading. Knowing this, helps me determine that it will be important to spend a few early lessons practicing characterization and making inferences about what type of person Jonas is so that we can compare and contrast once we’ve gathered enough data. |

Knowing these details and literacy targets helps me to make strategic decisions about graphic organizers, response to literature questions, and different activities that I want to use throughout the novel.

Step 8: Identifying Formative Assessments

We are going to commit all of the weeks to the study of a novel together. I can justify this with feelings and my knowledge that reading together and the academic discussion that this spurs are, in themselves, enough to merit this. I do not believe, however, that this is urgent, equitable teaching. It is incredibly important that I am consistently measuring the effectiveness of this unit and my instruction within it.

Here are some ways that you can assess your students throughout the novel study:

- Weekly (or bi-weekly, meaning twice a week) response to literature questions. These are critical analysis prompts that support students in identifying and analyzing the author’s moves and how they build (ultimately) towards theme. An early RTL question might be: “What kind of person is Jonas? How does Lois Lowry characterize Jonas? Give and explain at least three details directly from the text that support your claim.”

- Vocabulary and Grammar quizzes. Just because this is a novel unit, don’t think that I’ve forgotten about measuring this gateway skills! I usually have a vocab/grammar quiz or task every two weeks.

- Post it note exit tickets. In between RTLs, I also make space for students to demonstrate formative growth in small ways with post-it notes and index cards. Here are some other active participation strategies for exit tickets!

- Essays/Projects: These larger summative assessments are infrequent in the novel, but are still strong opportunities for students to demonstrate larger understanding and literacy target mastery.

- Student Centered Discussions/Socratics: These can happen on so many levels throughout your unit. Depending on the literacy strategies and standards that you are focusing on, you may choose more formal rubric-rated discussions or many informal small-group discussions. See this post to learn more about how to ensure strong student-centered discussion at any altitude.

Step 9: Map Your Unit

And now it is time to map it out! I prefer to use a calendar so that I can get clear on what’s possible where and what makes sense (and to ensure I do not plan over a holiday or teacher PD day). Additionally, this allows me to get clear on when I might insert larger and more significant formative assessments.

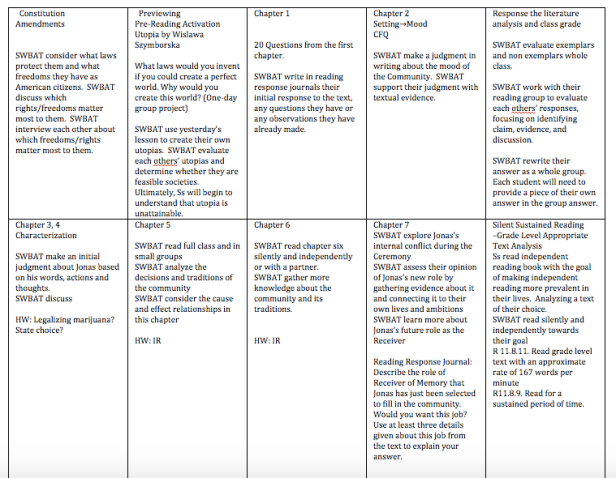

Check out this screen shot of the first weeks of the Giver. You can click here to see a long term plan and get a clearer idea of the unit overview and map.

This is hardly a complete series of steps. For more support and conversation around planning a novel, email me at Dale.Markey@teachforamerica.org to set up a planning date!

Read on! Plan on!