Writing Groups: Building Agency and Community Among Young Writers

If we’re truly serious about dramatically increasing the amount of writing and speaking that students are doing in our classrooms in order to build a critical mass of exposure, then it is essential that we’re able to build student confidence and provide time and structure to share and develop self-generated writing.

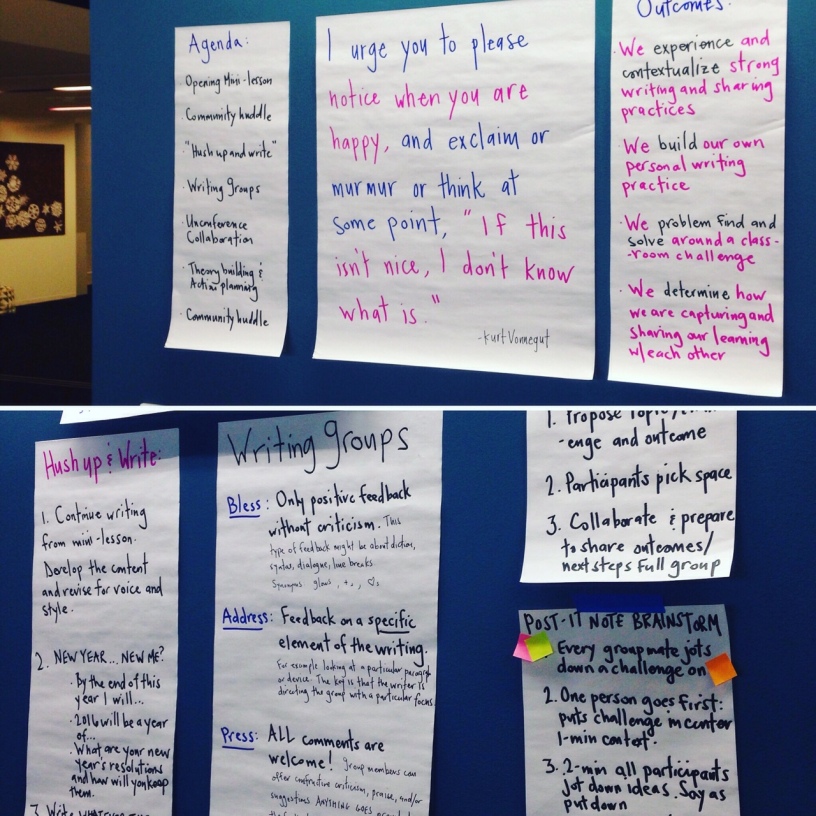

Here’s the overview of writing groups as Kelly Gallagher’s students practice them in his classroom:

- They meet every Thursday for 30 minutes.

- Each group consists of five students of mixed gender and ability.

- All written pieces brought to the writing groups are self-generated by the students

- For each writing group, students are asked to bring either a new draft or an old piece they have significantly revised.

- They are also asked to bring copies of their pieces for each of the other members of their groups. If it’s a group of five, the student should bring four.

- Once in the groups, each student takes a turn sharing his or her piece with the other members of the writing group.

- When it’s a student’s turn to share, he or she distributes copies of it to the other group members and, before reading it aloud to the other group members, indicates the level of response he or she would like from peers. The student asks the group to provide one of the following three levels of response (these originated from the National Writing Project):

- Bless: When a student requests “bless,” she is asking peers to share only what they like about the paper. Synonymous with “glows” or “+”, this type of feedback might include diction, syntax, sequencing, introduction/conclusion, impactful use of dialogue or line breaks. Bless means only positive feedback without criticism.

- Address: Upon making a request for “address,” he is asking for classmates to look at a very specific element of the paper. A student may want his peers to look closely to a particular section he is struggling with or the clarity of symbolism throughout the piece. The key is that the student is dictating exactly where in the paper he would like his group to focus their feedback.

- Press: When a student requests a “press,” she is indicating that ALL comments are welcome. The group members can offer constructive criticism, praise, and/or suggestions. Anything goes—provided the feedback helps the writer to make the paper better.

Here’s an example of what this might look like in action:

Let’s say it’s Antwan’s turn to share his piece with his writing group. He hands out his copies to the group, and because he’s a reluctant writer, he asks his group to “bless” his paper. After he hands out his paper, Antwan reads his paper aloud to his group, who follow along annotating and jotting down “blesses”. When Antwan finishes reading, he waits silently for 2-3 minutes while his group members revisit his paper, highlighting the strengths. They do all of this silently, and then grab some strips of precut paper (quarter sheets) and write their comments to Antwan.

When each classmate has had the chance to write his or her own comments for Antwan, the conversation begins. Antwan remains silent while each group member—one at a time—shares his or her thinking aloud with the group. Once everyone has shared their “blesses”, Antwan is then invited to respond and synthesize his takeaways. Antwan can also send the conversation in a new direction. After this initial response, the conversation is open—anyone can share his or her thinking. When the conversation runs its course, the group members pass their comment sheets to Antwan, who collects them and staples them to his paper. If Antwan wants to revisit the paper later in the year, he will have these written notes attached to his draft to jog his memory. The group then moves to the next writer!

Here are some quick suggestions if you’re interested in setting up a similar group in your own classroom:

- Model how the groups work. We can never simply give students instructions or a handout that explains a process and expect them to understand and be invested in it. What can be incredibly powerful is to model it. If you’re lucky, you can do this live with your entire department for all of your students. Or you can video tape yourself with colleagues afterschool and show it to your students, pausing and commenting throughout.

- Do not begin the writing groups too early in the year. It’s also important that students have foundational trust—with you, each other, and WRITING—before you stick them in year-long groups. Gallagher usually starts his groups during second quarter of the year.

- The teacher should select the writing groups, taking into careful consideration the makeup of each group. Gallagher mixes genders because boys and girls tend to think differently. He also mixes ability—making sure each group has access to at least one stronger writer. He is strategic about placing reluctant writers with students who will be nurturing.

- Writing groups should stay together for the remainder of the year. Many groups (like communities of practice) start off a bit shy and awkward. But the power of meeting weekly is that it allows for the group members to bond and grow together. While students might initially start with mostly “bless” requests, you’ll notice over the months that will shift as students become more comfortable with one another.

Challenge is not unheard of in any situation in which humans are working together in groups. Here are some common challenges and possible ways to address the problem:

- A group has trouble generating a conversation for an entire class period. Sit with the group. When the conversation lulls, insert a comment or question to restart the conversation. Modeling is key, also debriefing the discussion (the process and outcome) can help students to understand what is helpful and what skills they are building in supporting one another.

- A student shows up unprepared for the group discussion. Adopt a “three strikes and you’re out” policy. For the first and second offense, students can participate without bringing a piece to share—there is value to engaging in the conversation in order to build investment and leverage the beautiful effects of peer pressure. If it becomes habitual, remove the student and have them silently draft while the groups are meeting. This is usually enough to get the student back on track.

- A student is absent on writing group day. If a student misses writing group day but shows up the next day with a draft, give her half credit. The student cannot receive full credit unless she also participates in the discussion, since that’s where much of the value lies. Make sure you explain this to your students when you introduce writing groups for the first time.

- A student keeps writing the exact same type of paper each week (e.g. a student shows up with a poem every week and doesn’t stretch himself into other writing discourses). While students should write freely and should feel encouraged to go deep on topics, discourses, and genres, they should do this with an end goal in mind (either of a multi-genre portfolio or of diversifying their writing). A student who writes a poem every week will not be prepared for their end-of-year portfolio or writing goals. You might choose a way for students to track their writing trends at the front of their notebook/folder so that they can be aware of this/so that you can harken back to the goals ongoing.

- A student writes way too much for the group to respond to in a short time. If you’ve taught middle or high school writing, chances are you’ve run into the student who is working on his own fan fiction or short novel. I had a student, Tyler, who wanted to use writing groups as an opportunity to get feedback on his novel. Every time his group met, he had 15 pages for them to read! To streamline the discussion, I had Tyler choose an excerpt (up to two pages) from his weekly work that his group could bless/press/address.

- A student shows up with his writing piece but doesn’t have copies for his partners to track while he shares. Many of my students did not have access to printers at home. They did have access to the school’s media center to print for $0.05 a page; they also could come to my classroom after school the day before or before school that morning to print for free. Yes, that means a lot of ink and paper, but ink and paper is an easy holiday present/fundraiser!

And, of course, grading…

Gallagher doesn’t score all of the papers. There is no way that he could possibly keep up with the volume of the writing! The point here is to set students up to write independently and use the group to hold them accountable and build their agency and confidence. It’s to help them develop their identity as writers who write regularly. This is more likely to happen if the teacher DOESN’T grade every single thing students write. As Gallagher shares: “Grading doesn’t make my students better writers. Lots of practice coupled with meaningful feedback makes my students better writers.” Instead, moving between writing groups on these sacred Thursdays, stamping drafts with the date (as well as modeling strong feedback), he is able to validate their effort and later give points for the dates they accumulate. Many will never been graded, and others will be selected and assessed as part of their end-of-year portfolios.