Over the break I read Kelly Gallagher’s newest book, In the Best Interest of Students, and had, as is not uncommon when reading anything he’s written, a few epiphanies about my continued failures in the world of teaching. Like all of our failures in pursuit of educational equity, these were well-intentioned and aimed at providing my students with the skills and educational experience that I believed would open pathways of opportunity and joy through literacy. And while my (and I would bet your) students read a lot and wrote a lot, I realize now that I was doing took away the most cognitively rigorous and rewarding part of each essay and project assigned: I was picking the questions for students rather than supporting them in developing their own skills in questioning and inquiry.

The rest of this post will be about breaking the long-valued teacher practice of question choosing and how to move to a form of skill-building and assessment that not only offers students an opportunity to choose the question they research and write about in argumentative essays, but ALSO brings the teacher/reader/grader joy.

We, teachers, often approach argument like there is an argument when there is no argument.

When we ask students to make an argument defending the central theme found in To Kill a Mockingbird (Lee 1960) or the most influential contribution of the Egyptian civilization, for example, there is not much of an argument there. We have, in effect, asked the question “Can you find the main theme in the novel?” or “Can you identify the main contribution of the Egyptians?” and students set off to scour the book and primary sources for evidence to support our question. This line of questioning feels superficial and inauthentic, especially when students know that they can find it on Schmoop.com or under the chapter summary. When a student makes a claim that “It takes courage to stand up to racism” is a main theme found in To Kill A Mockingbird, there is no real argument there.

It’s a little thing to answer someone else’s argument question; it’s a big thing to initiate your own idea and craft an argument from it. This is the kind of argumentative thinking we want our students to develop.

Argument doesn’t start with a claim; argument starts with data.

When crafting an argument, students often begin by forming claims and then they look back to the text to find data that supports their claims. Gallagher (and Hillocks) argue that this approach is backward. What is more accurate is to support our students in starting by immersing themselves in lots of data, and, as they work through the data, they should take note of the interesting claims and assertions beginning to emerge.

To consider how this might look in your classroom, let’s look at the case of Steve Avery, the Wisconsin man and focus of the Netflix documentary series Making a Murderer. As we watch the documentary, the story of Avery’s experience with law enforcement and the complicated web between police and prosecution unfolds. Here is the sequence of that evolution through the first two episodes:

- Avery is poor, white, and lives in a small town. His family is not really part of the community. They run a junkyard at the end of a long road.

- Avery is marked as “trouble” by law enforcement—a number of disorderly conducts and running his cousin off the road and pointing a shotgun at her for spreading rumors about him. His cousin is close friends with a woman that works for law enforcement.

- A young mother is sexually assaulted while running alone on the beach and describes being attacked by a man with long blond hair and beard. Avery is pursued.

- Despite Avery’s having an alibi and it becoming clear that the police investigator created a composite while in possession of previous mug shot photos of Avery and their being no conclusive evidence that Avery was on the beach that day, he is convicted of sexual assault and sentenced to 32 years in prison.

- Avery maintains his innocence during his entire prison stay.

- In 2001, the Innocence Project of Wisconsin takes on his case and with new DNA evidence is able to show conclusively that Avery was not guilty of the attack, and instead it committed by another well-known felon of violent assault, Gregory Allen. In 1985, Allen had been dismissed by people within the police who indicted Avery as the undisputed attacker.

- Avery, once free from prison, vows to make sure that he reveals the corruption within the Manitowoc Police Department.

While watching these first couple of episodes some big questions begin to come up for the viewer—questions that might eventually lead to some fascinating arguments (ones I cannot wait to read about and have over the dinner table in the weeks to come). As Hillocks and Gallagher note, teachers should try “to find data sets that require some interpretation and give rise to question and genuine thinking. Attempts to answer these questions become hypotheses, possible future thesis statements that we may eventually write about after further investigation. That is to say, the process of working through an argument is the process of inquiry” (Hillocks 2011, xxii). This is the opposite of the traditional approach where a student starts with a claim and then looks for evidence to support that claim. Instead, Hillocks and Gallagher suggest that students should START WITH INQUIRY. They should explore a text (or series of texts) and the issues within and surrounding it until interesting arguments begin to emerge. For example, given the Avery story in the first couple of episodes of Making a Murderer, here are some arguments that emerge that might merit deeper exploration:

- Is Steve Avery’s case one of the most shocking instances of police corruption?

- Is more police/law enforcement oversight needed in our country?

- How common is this sort of clear targeting of individuals as criminals in our system?

- How is it possible that in the face of what seems like clear miscarriage of justice that a man is convicted?

- Given the prevalence and intent of the media, is it still possible to have a fair trial where one is innocent until proven guilty?

Some of these questions lead to judgment arguments, while others lead to policy arguments. All of them were generated after being immersed in data. I can imagine modeling this process with students and then challenging them with developing stories worthy of tracking over time. Here are some stories that students could have tracked in the past year:

- Tamir Rice Story

- The Benghazi Attack and the subsequent hearings

- The success of the Black Lives Matter movement and the controversy around the All Lives Matter response

- Planned Parenthood and the conversation around fetal tissue sales

- The Paris Attack and the Trump response

- The San Bernadino massacre and the definition of domestic terrorism (or the place in which this mass shooting fits in the year of shootings in the United States)

All of these stories can be tracked over time, threads can be pulled forward and backward. For students who have trouble deciding where to begin searching for interesting data, you might have them start with The Learning Network (on The New York Times website). Michael Gonchar has posted over 200 prompts for argumentative writing following broad categories from Education to Gender Issues to Politics and the Legal System. You can leverage this list to show your students how to develop questions that may lead to interesting arguments.

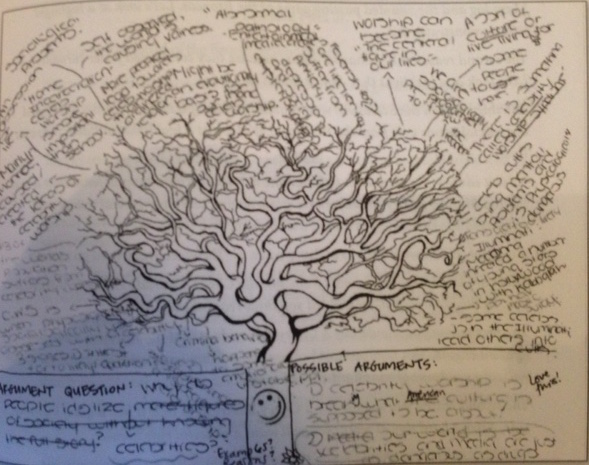

You can use this list to read a series of articles about the same topic and develop a series of questions worthy of deeper exploration. After reading a series of articles and even reading the comments section (!!!), students are then able to visualize their thinking by using a “data” tree. See this student’s data tree responding to the initial question “Why do people idolize celebrities?”

You can see, while she starts with an article of that name, she branches out immersing herself in a large data set (in this case related articles) and other ideas catch her eye; she jots them down on her data tree. At the end of this reading, she can step back and see a number of possible arguments emerging and choose one that she’s truly intrigued by. In this case: “Celebrity worship is breaking what American culture is supposed to be about.” You’ll note that this argument is NOT the argument that she began with!

I would be surprised if in your entire educational career you haven’t had the experience of getting to the end of a paper and realizing that your concluding paragraph argues an evolved and DIFFERENT thesis than you started with. I remember having a tutor at Oxford that told me: “Where you end up in the last line of your first draft; that’s where you should start your paper.” And that is, in many ways, what Gallagher is showing us. Only by working through the data set, truly picking through the different arguments that have already been made, analyzing, corroborating and refuting them, do we emerge with our true and unique argument.

We can do this same type of inquiry in literary analysis too.

Like Gallagher, author and educator Linda Christensen also noticed herself functioning under the modus operandi of thesis first, then find evidence. This was true particularly during novel study. What she found was “[A student’s] thesis didn’t fit their facts. It sounded great, but couldn’t find any purchase once they started writing.” She decided to flip her model.

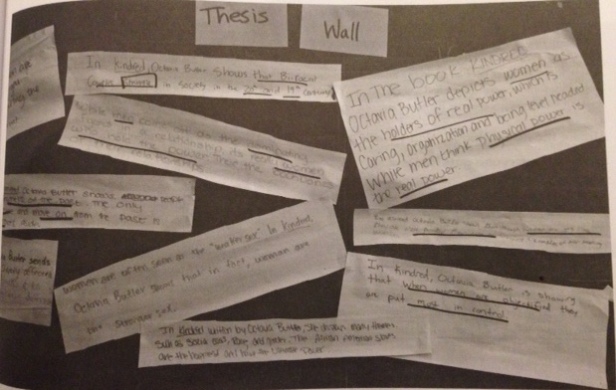

While she reads a novel with her students, she has them pull out themes and topics along the way and students keep those themes up on a theme/topic wall. While they read, they will jot down evidence or instances of events/symbols/literary devices that either support a theme/topic of interest or diverge and create a new category and share it on the wall. This creates a visual map and account for students that they can leverage (like a data tree) in order to develop their personal thesis at the end of the novel. Check out Chapter 3: Writing Essays in Teaching for Joy and Justice for more in depth discussion of process (Christensen 2009, 119-159).

Avoid paper grading Groundhog Day. Have students discover their unique arguments through inquiry.

Don’t have students start with a question and go find evidence. Have them discover arguments through the inquiry process! Having students start with inquiry before they generate arguments works in all contents areas. If I were an American history teacher and my students were studying the Civil War, I would want them to read widely about the Civil War before generating their arguments. A students that develop their arguments from questions after doing extensive reading are going to produce much better papers and engage in much deeper and authentic reading than those searching myopically for evidence that supports a predetermined lens on the content.

When students are taught to approach argument through inquiry, good things happen—for students and teachers. Students choose topics that merit deeper reading and argument; they gain ownership over their position and see their paper as an opportunity to share their opinion. And you, as the teacher, are not stuck reading the same paper and the same argument over and over again.

Resources:

Gallagher, Kelly. In the Best Interest Of Students: Staying True to What Works in the ELA Classroom. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers, 2015. Print.

Christensen, Linda. Teaching For Joy and Justice, Reimagining the Language Arts Classroom. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Rethinking Schools, 2009. Print.

The Learning Network. The New York Times. http://learning.blogs.nytimes.com/. January, 5, 2016.